Color, 1974, 105m.

Directed by Jack Hazan

Starring David Hockney, Peter Schlesinger, Celia Birtwell, Mo McDermott, Ossie Clark, Henry Geldzahler, Betty Freeman

BFI (Blu-Ray & DVD) (UK R0 HD/PAL) / WS (1.85:1) (16:9), First Run (US R1 NTSC) / WS (1.85:1)

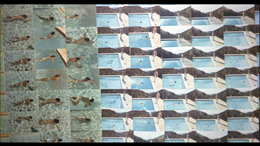

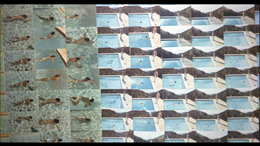

The pop art movement in the 1950s produced many highly influential artists both in England and America, with names like Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein becoming famous for their modern, sometimes perplexing looks at modern pop culture. One of England’s most enduring stars from the period remains David Hockney, whose 1967 painting “A Bigger Splash” is one of the most famous examples of his fondness for bright, artificial looks at natural elements, frequently water. Hockney himself often denied being part of the pop art movement, but there’s no question it would be a very different chapter in art history without him.

The pop art movement in the 1950s produced many highly influential artists both in England and America, with names like Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein becoming famous for their modern, sometimes perplexing looks at modern pop culture. One of England’s most enduring stars from the period remains David Hockney, whose 1967 painting “A Bigger Splash” is one of the most famous examples of his fondness for bright, artificial looks at natural elements, frequently water. Hockney himself often denied being part of the pop art movement, but there’s no question it would be a very different chapter in art history without him.

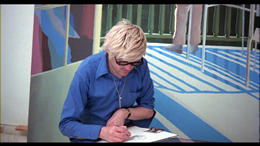

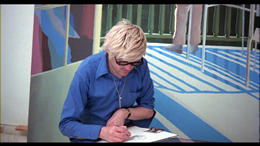

That painting also inspired the name of a 1974 film forged under highly unusual circumstances. Filmmaker Jack Hazan, a documentarian with a few shorts under his belt who went on to helm the terrific Rude Boy with The Clash, was granted access to Hockney and the other people in his life for a period of two years, during which the non-actors essentially recreated pivotal moments which became reflected in Hockney’s paintings. There isn’t much in the way of a traditional storyline, but the gist here is that Hockney’s process of creating the titular painting is disrupted by a breakup with his lover, Peter Schlesinger (also playing himself), while various other figures in the art and fashion worlds swirl around him interspersed with dreamlike scenes of Hockney’s subjects dissolving into and out of their painted counterparts while he works on his canvases.

At the time A Bigger Splash was released, the film was mainly pegged in art house circles as gay title in the same vein as some of Paul Morrissey’s films for Andy Warhol like Lonesome Cowboys and Trash. That label is fairly understandable, as the Warhol/Morrissey influence is undeniable here (along with a few flourishes of Michelangelo Antonioni and William Klein thrown in for good measure), coupled with the fact that virtually every male in the film disrobes at one point or another. However, one extended sex scene aside, this is definitely more like a life drawing class than a softcore film, and as the vague theatrical trailer indicates, this must have been very difficult to market in a climate before films like Nighthawks and the same year’s A Very Natural Thing. Anyone unfamiliar with the basics of 20th century art history  will be baffled by much of the environment here, but if you just sit back and don’t expect a tightly woven storyline to emerge, it’s a poetic and often delightfully experimental little mood piece. However, one surprising flaw here is the underwhelming music score by Patrick Gowers, who had done far more interesting work on The Virgin and the Gypsy a few years earlier and would go on to his greatest achievements for the Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes TV series. Had this film been made a few years later, it’s tempting to imagine the wonders Michael Nyman could have done with it. Despite Hockney’s oft-stated shock at seeing his life half-fictionalized onscreen, this hardly proved to be the last time he would step before the cameras, as he was also the subject of Hockney at the Tate in 1988 and David Hockney: A Bigger Picture in 2009.

will be baffled by much of the environment here, but if you just sit back and don’t expect a tightly woven storyline to emerge, it’s a poetic and often delightfully experimental little mood piece. However, one surprising flaw here is the underwhelming music score by Patrick Gowers, who had done far more interesting work on The Virgin and the Gypsy a few years earlier and would go on to his greatest achievements for the Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes TV series. Had this film been made a few years later, it’s tempting to imagine the wonders Michael Nyman could have done with it. Despite Hockney’s oft-stated shock at seeing his life half-fictionalized onscreen, this hardly proved to be the last time he would step before the cameras, as he was also the subject of Hockney at the Tate in 1988 and David Hockney: A Bigger Picture in 2009.

Probably because of the name value of its subject and the fleshy promotional artwork, A Bigger Splash has been availa ble as a below-the-radar title on home video since the days of VHS, when it made the rounds in a very blurry transfer taken from a U.S. release print (one of New Line’s earlier titles, back when they were getting John Waters off the ground). A non-anamorphic widescreen DVD appeared in America from First Run, but it’s a pretty disappointing affair with a brief text Q&A with the director and little else to distinguish it. Fortunately the BFI dual-format release finally gets it right with a sparkling new HD transfer, featuring far more impressive colors which give punch to the many compositions intended to mimic Hockey’s paintings. Apart from a few darker scenes shot in very low light that will always look pretty underwhelming, it’s a very impressive, film-like presentation without any distracting digital mucking around to try to make it too pretty. Optional English subtitles are also included for the original mono soundtrack. Two video extras are included on the Blu-Ray disc, kicking off with the 25-minute “Love’s Presentation” from 1966. Directed by James Scott, it’s a free-form piece built around the subtitled concept of “fourteen poems of CP Cavafy chosen and illustrated by David Hockney.” This means we get to see monochromatic footage of Hockney crafting a series of prints while offering voiceover about the process. Made six years later, David Pearce’s “Portrait of David Hockney” runs a scant 13 minutes and features atmospheric shots of the painter at work in his apartment, particularly in progress on a painting of Ossie Clark (also seen in the main feature). Sort of a “day in the life” snapshot, it’s a perfect companion piece to the more challenging main attraction on the disc. The DVD contains all of these extras in standard def and also throws in an SD interview with Hazan, who talks about everything from getting Hockney to agree to the project to the state of his personal and professional life at the time, which had to be dramatically sculpted to fit the final form of the film. The enclosed illustrated booklet contains a John Wyver essay, “Ways of Looking,” about the film’s complex relationship with “reality” and its celebrity subject, while a Philip French review from Sight and Sound offers a more immediate ‘70s perspective. A Hazan bio by Michael Brooke and notes on “Love’s Presentation” by William Fowler and an archival 1977 piece on “Portrait of David Hockney” round out the set.

ble as a below-the-radar title on home video since the days of VHS, when it made the rounds in a very blurry transfer taken from a U.S. release print (one of New Line’s earlier titles, back when they were getting John Waters off the ground). A non-anamorphic widescreen DVD appeared in America from First Run, but it’s a pretty disappointing affair with a brief text Q&A with the director and little else to distinguish it. Fortunately the BFI dual-format release finally gets it right with a sparkling new HD transfer, featuring far more impressive colors which give punch to the many compositions intended to mimic Hockey’s paintings. Apart from a few darker scenes shot in very low light that will always look pretty underwhelming, it’s a very impressive, film-like presentation without any distracting digital mucking around to try to make it too pretty. Optional English subtitles are also included for the original mono soundtrack. Two video extras are included on the Blu-Ray disc, kicking off with the 25-minute “Love’s Presentation” from 1966. Directed by James Scott, it’s a free-form piece built around the subtitled concept of “fourteen poems of CP Cavafy chosen and illustrated by David Hockney.” This means we get to see monochromatic footage of Hockney crafting a series of prints while offering voiceover about the process. Made six years later, David Pearce’s “Portrait of David Hockney” runs a scant 13 minutes and features atmospheric shots of the painter at work in his apartment, particularly in progress on a painting of Ossie Clark (also seen in the main feature). Sort of a “day in the life” snapshot, it’s a perfect companion piece to the more challenging main attraction on the disc. The DVD contains all of these extras in standard def and also throws in an SD interview with Hazan, who talks about everything from getting Hockney to agree to the project to the state of his personal and professional life at the time, which had to be dramatically sculpted to fit the final form of the film. The enclosed illustrated booklet contains a John Wyver essay, “Ways of Looking,” about the film’s complex relationship with “reality” and its celebrity subject, while a Philip French review from Sight and Sound offers a more immediate ‘70s perspective. A Hazan bio by Michael Brooke and notes on “Love’s Presentation” by William Fowler and an archival 1977 piece on “Portrait of David Hockney” round out the set.

Reviewed on January 16, 2012.